EDGAR DEGAS & CHLOE FLAMANT

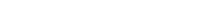

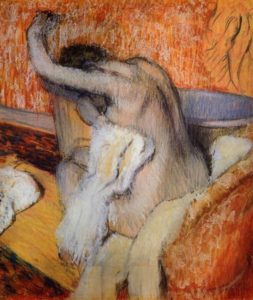

My name is Chloe Flamant. That’s me in a pastel Monsieur Degas made in 1894. The likeness of my backside is very good. Degas called it, After the Bath, woman drying her neck. I know, not the greatest title in the world; he saved his genius for the canvas.

In 1894, I was in the corps de ballet of the Paris Opéra Ballet. The girls in the corps were called “the little rats.” Degas was a little nicer about it; he called me his “little monkey girl.”

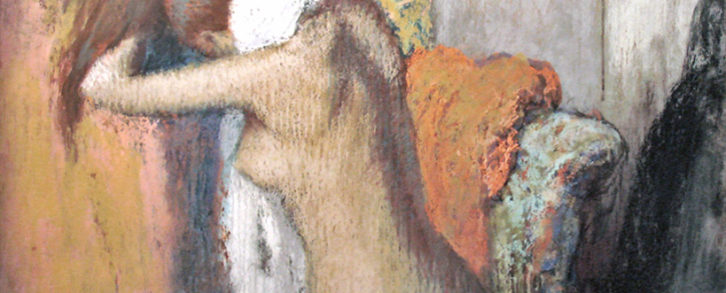

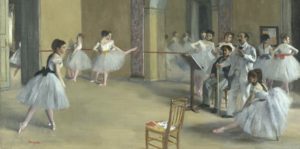

Ballet at the Paris Opera – 1877-1878

I posed for Degas more times than I can remember. My backside appears in many of his works. When I posed in his studio, Degas did what men do—especially artists—he talked about himself. His life story had some twists, some as contorted as the poses he put his models into.

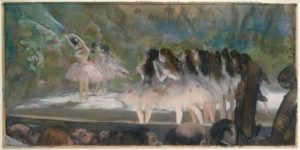

After the Bath – 1896

After being raised in an aristocratic family—Degas’s father was a French-Italian banker, his mother was a French-Creole from a rich New Orleans family—Degas rebelled against belonging to the haute bourgeois. He wanted to be an artiste!

His first paintings were very realistic. My favorite of these is The Orchestra at the Opera with his friend Désiré Dihau in the foreground, the bassoonist at the Paris Opéra Ballet.

The Orchestra at the Opera – 1870

I like it because of the ballerinas in the background and what they foretell. Degas would soon push past the musicians, past the dancers on stage, and into the wings where he became fascinated by dancers and their backstage world.

Le foyer de la danse – 1872

One of his first backstage painting was Le Foyer de la danse. The large room in the opera house was a rehearsal space and a place for rich patrons on the prowl for mistresses.

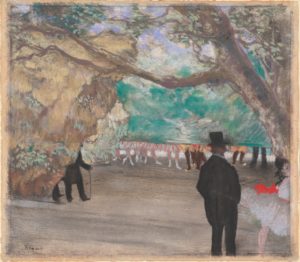

Unlike the above painting showing a mother pimping her daughter to one of the “protectors,” Degas painted lurking protectors eyeing ballerinas from a different perspective in The Curtain.

The Curtain – 1880

In art and life, Degas looked at the world differently. He never married or had a mistress and avoided alcohol. Work was everything. His skewed take on life was why I liked him. He didn’t see the world in a proper Victorian frame, all front and center. He wanted to capture le tranche de vie—slice-of-life—the more slice-of-life, the more ordinary the better.

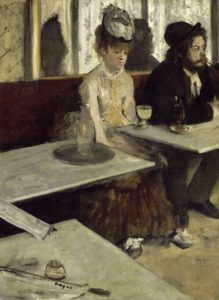

Absinthe – 1876

His painting, Absinthe, was a huge scandal for that reason. The critics called it ugly, disgusting, and a blow to Victorian morals. Degas disagreed. He saw beauty in small moments. He found humanity in the mundane. It’s why he insisted he was a “realist” and not an “impressionist.”

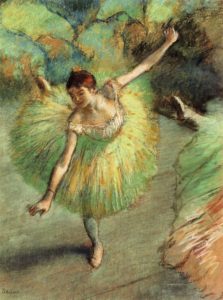

Fate disagreed. In his 40s, Degas began to slowly go blind. His failing eyesight robbed him of his sense of line and detail. It turned him from painting with oil to pastels. Like fancy crayons, pastels became the magic wands that allowed him to create what he saw best: light and color.

Dancer Tilting – 1883

Dancer friends of mine, who also posed for Degas, said that his bad eyesight was God’s punishment for hating women. I didn’t agree, even though I once heard Degas say to a fellow artist, “I have perhaps too often considered woman as an animal. I show them without their coquetry, in the state of animals cleaning themselves.”

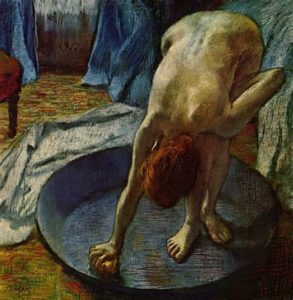

The Tub – 1886

I knew better. It was Degas trying to sound tough, the monk who had taken a vow of celibacy and had to insult what he denied himself. To me, Degas was more like a woman than a man. When he worked, he was like a mother with all five senses locked on her baby. With each stroke of his pastel, he gave his “animals” life.

I believe it was his fixation on the quietist attitude and smallest human gesture that led him from the backstage world of ballerinas to the tinier stage of the basin and tub where women perform a more primitive dance.

The Tub – 1886

Around the time I met Degas, his skewed point of view was taking its strangest twist. He no longer looked us in the eye. He turned our faces away and rendered our backsides. It was as if he was looking at the world through a keyhole. My nickname for him was “Saint Voyeur.”

After the Bath (Woman Drying Herself)– 1895-1900

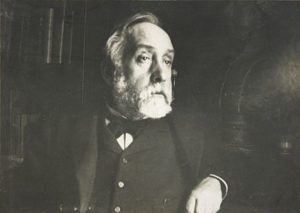

When I last saw Degas before he died in 1917, he told me that only one of his works hung in a museum. It was an early, realistic painting: A Cotton Office in New Orleans. He had painted it while visiting his mother’s family in America. He joked that if all of his work disappeared except for that one piece, his dying wish would come true. He would be remembered as a realist.

A Cotton Office in New Orleans – 1873

Thank God Saint Voyeur didn’t get his wish. In 1919, when a large body of Degas’s work went to auction, it sold at exorbitant prices. Like it or not, Degas became a famous impressionist.

In French, we have a word: flâneur. A flâneur is someone who strolls the boulevards of Paris and takes in the human circus. Degas was the flâneur of flâneurs who took flâneurism one step further. His work makes us stop and take a close, intimate look at our fellow “animals.” The blind man shows us how to drink with our eyes.

If you’d like to be a flâneur in 1894 Paris, and walk with the likes of Degas, me, and the naughty Toulouse-Lautrec, you can find us in Blowback ’94. And I promise, you’ll get to watch Saint Voyeur create his pastel of me, After the Bath, woman drying her neck.

Edgar Degas – 1895